- Home

- Noelle Harrison

The Island Girls: A heartbreaking historical novel Page 2

The Island Girls: A heartbreaking historical novel Read online

Page 2

She hadn’t even smelt the bread burning because she’d been lost deep inside Daddy’s boyhood copy of Treasure Island. It was Kate who came tearing into the kitchen and flung the oven open.

‘Susie! The bread!’

Susannah jumped up from the table. ‘Oh no, oh shoot, Katie!’

‘Quick! Hide the book. She could be back any moment,’ Kate said, opening the door and flapping the tea towel to clear the kitchen of the black billows of smoke.

‘Are they ruined?’ Susannah asked, stuffing the book under a cushion.

Kate took out the trays of blackened loaves. Slipped the oven gloves off.

‘I’d say so,’ she said, smothering a giggle.

‘Why are you laughing? I’ll get the brush handle for this,’ Susannah said despairingly, but her sister’s giggles were infectious. A laugh bubbled up inside her. Kate looked so funny with threads of lace hanging off her skirt, hair all wild, and well – here Susannah was again, being the dreamer as Mother always complained.

‘I’ll make some pancakes, they’re quick enough,’ Kate said. ‘Tell her it’s my fault the others burnt. I was watching the bread while you were out getting the washing down.’ Kate waved at the window to the sheets flapping on the line outside. ‘She won’t hit me!’

It was true. Their mom clearly favoured Kate. Well, any mother would. Kate was so good at everything their mother viewed as important – lace-making, sewing, cooking and gardening. Susannah tried to do things right, but she got caught up in her books. She’d decide to read to the end of a chapter, put the book down and help Kate out, but then the story would kidnap her and hours might pass before she realised Kate had done all their domestic tasks on her own. Her sister never told on her, but often their mother would catch Susannah out. Curled up on her bed, buried in a book. A loud slap on the leg was her resounding wake-up call to join the ‘real world’ as their mother called it.

‘Vinalhaven isn’t the real world, Mom,’ she’d talk back, her leg and dignity smarting from the slap. ‘The real world is what’s happening out there.’ She waved her arm towards the window and the view of the blustery Atlantic Ocean, as the daily craving to know what was really going on beyond the borders of the tiny island dug into her heart.

‘That’s where you’re wrong, my girl,’ her mother told her. ‘The real world is right inside these four walls, where you, your sister and I have to make our living, and provide for ourselves all on our own.’

Susannah immediately felt guilty. She always did when her mother reminded her how much she had to sacrifice to look after her two daughters with no husband to help. What good were books when you had to make a living on the island of Vinalhaven, miles from the mainland, let alone an actual city?

Susannah picked up the laundry basket.

‘She won’t believe you burnt them.’ Susannah was glum now as she spoke to Kate. Her backside was still sore from yesterday’s smack for dropping one of their precious eggs.

But Kate wasn’t listening. She was all a bustle, cleaning out the burnt tins and getting together everything she needed to fix Susannah’s mess.

Susannah headed out into the garden, glad to be outside the house. It was a blustery day and the sheets flapped around her in the wind. She walked through them, imagining she was wandering the streets of a bazaar and these were brightly coloured banners. She closed her eyes, went to a place her daddy had been during the war. Morocco. She could smell the street vendors’ exotic foods, hear the strange language they were speaking, see the beautiful women with dark eyes, beauty concealed behind veils. She had never forgotten the stories her daddy told her on his one visit home. If she squeezed her eyes shut, really tight, he was right before her. Come on, my little Susie. One hand for her, one hand for Kate. Daddy had his girls again and he was going to show them the world. Yes, she could hear the cries of the vendors now, smell the spices and the heat of Casablanca as Daddy took them on an adventure. Weaving through tiny streets and alleys. Searching for ancient wisdom in a land far older than their own.

A sheet slapped her in the face, and she opened her eyes, her dream disappearing fast into the blue western sky. She gazed out to sea. This was where they lived. Perched on a rise of land, the back garden opening out onto a rocky slope all the way down to the Atlantic, and in the other direction blueberry bushes, and pine woods.

Susannah pulled down one of the sheets and wrapped it around her. She was the daughter of a gypsy. She drew the sheet across her nose and mouth, and made her eyes big and round. What would it be like to live in a tent in the desert? To ride a camel? Would she dance with her sister around the desert fires? What would they eat? She didn’t think it would be pancakes. Maybe fruit? Sweet and juicy, something like plums.

‘Susannah! What are you doing, girl? You’re dragging the sheet in all the dirt.’

Her mother loomed over her, arms crossed, frowning. Always frowning at Susannah. She was tall too, the only physical feature Susannah had inherited from her mother. It was Kate who shared the same fair hair and blue eyes as their mother. Although her sister never looked as severe as their mother did now: the rosebud contours of her lips drawn into a thin line of disapproval.

‘Sorry, Mom, I was hanging the laundry,’ Susannah said, not daring to look her mother in the eye.

‘Well, it sure looks a funny way to be doing it.’ Her mother grabbed the now dirty sheet from her hands. ‘It’ll have to be washed all over again. Not that I don’t have enough to be doing.’

This was the anthem of their childhood. All the chores her mother had to be doing. But for who? That’s what Susannah wanted to shout out. She and Kate didn’t care if the house was less than perfect.

‘Mom likes to keep standards up,’ Kate had tried to explain to Susannah when she’d complained about all their back-breaking chores all summer long.

‘None of the other kids on the island have to work so hard,’ Susannah said. ‘They get to have fun, swimming and all.’

‘But they’ve all got daddies,’ Kate said to her. ‘Mom has to work extra hard at looking after us so we don’t starve. That’s why we’ve got to do the house for her, so she can lace.’

‘Well, I still don’t know why we’re doing so much work for just us three,’ Susannah continued to moan.

‘Because of the Olsens, silly!’ Kate had declared. ‘Daddy’s family could come over any time. She don’t want them to see her down.’

That was one thing all right. Their mom was proud, and Susannah admired her for that.

After their regular dinner of fish and potatoes, their mother relented on grounding Susannah for dirtying the sheets and let them out for the last few hours in the summer’s day. The two sisters ran like crazy down the stony track to Lane’s Island’s Bridge Cove. Susannah suggested they swim in the old quarry on Amherst, but Kate had said the woods were too scary when it started to get dark. She preferred to be out in the open, on the edge of their island and looking out at the ocean. All Susannah cared about was getting into the blessed cool water after the long hot day. She didn’t mind all the midges swarming around them as she hopped from foot to foot to get her shorts off. They never bit her anyway, only Kate.

The two girls ran into the water, squealing with delight. Susannah submerged herself immediately and began swimming out further from shore.

‘Don’t go too far,’ Kate called as she splashed about in the shallows.

Susannah was the stronger swimmer. Kate never ventured too far from land, even if it was calm like today. It was their daddy who’d taught Susannah how to swim, the summer he’d been back on leave. She’d been four, old enough, but Kate had been too little and their mother had refused to let her baby in the sea. Their mother never swam.

Susannah had never forgotten her daddy carrying her into the ocean with him until the sea was up to his shoulders and she felt it swaying all around her. She’d been scared and excited all at the same time. Safe in the knowledge her daddy would never let her sink to the bottom, but also

wanting to show him she was a brave girl. He had held her hands and her legs had swung out behind her, lifted by the buoyancy of the salty water.

‘Kick your legs, Susie!’ he had encouraged her. ‘Make waves!’ he’d laughed.

The first time he’d let her go, he hadn’t warned her and she had almost screamed with fright, but then he kept saying:

‘I’m here, Susie, right here; you can do it, my girl.’

The water was home right from the beginning. It carried her and she had trusted it. Began to swim all on her own, much to her daddy’s delight. She was a mermaid, flipping her tail, and diving beneath the surface. Following her father under the water, their red hair waving like sea flora, both their eyes open, bubbles all around them.

The last three summers, Susannah had been trying to teach Kate to swim. Susannah had wanted to pass on what she’d learnt from their daddy, but Kate never took to it like she had. Started screeching when Susannah pulled her too far out from the shore, declaring she didn’t like it when she couldn’t put her feet down on anything.

‘But that’s exactly what I love,’ Susannah had said in astonishment. ‘I feel so light!’

Susannah kept swimming. It hurt her heart to think of her daddy. She tried not to, but sometimes she just couldn’t help thinking about what had happened to him. Their mother had never spoken about details during the war. Just told the girls their daddy was never coming back, and Susannah couldn’t even remember exactly when that had been.

It was only at the beginning of this summer that Mrs Matlock, the librarian, had told her a little about what had happened to her daddy. Apart from the ocean, Vinalhaven’s small town library was Susannah’s favourite place to be. Often, she’d hide away for hours reading all the history books. There was plenty on the Civil War, and the history of English kings and queens but Susannah was looking to read about what had just happened in the world. When she’d drummed up enough confidence to ask Mrs Matlock, she’d been told the war was not history yet.

‘I’ve some old newspapers catalogued,’ she told Susannah, looking in surprise at her over the rim of her glasses. ‘But why would you want to be reading about something as terrible as the war? Wouldn’t you prefer a nice story book? Have you read Little Women? It’s a favourite of mine.’

Susannah had shook her head. ‘I want to know what happened,’ she’d said to Mrs Matlock.

It was as if the older woman knew without being asked. ‘Is it about your father?’ she said, her eyes gentle.

‘Did you know him?’

‘I sure did.’ Mrs Matlock smiled fondly. ‘Spent nearly as much time as you in this library when he was a boy.’

It pleased Susannah to hear this about her father. He had liked books too.

‘Has your mother never told you what happened to him?’

‘All I know is he was posted to North Africa,’ Susannah said. ‘He came back once on leave. But when he went back he got killed.’

Mrs Matlock nodded sadly. ‘Yes that’s right, your father was posted to North Africa after the Anglo-American occupation of Casablanca. But he didn’t die there. Your mother told me he was killed in action during the allied invasion from North Africa to southern Italy in 1944.’

Susannah sat quite still. North Africa. She remembered him telling her about the dry heat, the desert nights packed with stars. But Italy? She’d no idea her father’s life had ended there.

‘Has your mother never spoken to you on it?’

‘No,’ Susannah whispered.

‘Oh, Lord,’ Mrs Matlock said. ‘I do hope I haven’t spoken out of turn. How old are you now, Susannah?’

‘Eleven. Nearly twelve.’

‘Well, I guess you’re old enough.’

‘Where’s Casablanca?’ Susannah asked Mrs Matlock. She’d heard of the movie. Everyone had, but she had no idea where it was in northern Africa.

The librarian took down one of the big atlases and spread it open on one of the library tables. Susannah pored over the map until the library closed. By the time Mrs Matlock had locked the door and waved her goodbye, Susannah knew that Casablanca was situated facing the Atlantic Ocean on the north-western coast of Morocco. It was founded by Berbers in the seventh century BC and called Anfa. In the fifteenth century it was ruled by the Portuguese, and then the Spanish, from where it got its name – Casablanca – ‘white house’. Colonised again this time by the French, during the Second World War the city was part of French territory. Susannah traced her finger all the way from Casablanca across northern Africa to Tunisia, and the short blue leap of ocean over to the heel of Italy. She read that it was less than 1000 kilometres between Tunisia and Sicily. Susannah knew all this, but she still didn’t know how her father had died. Where in Italy? Had it been during the invasion of Rome? Or a skirmish with Germans in a small hillside village in southern Italy? Had her father’s end been a hero’s death?

Susannah stopped swimming now, and trod water. If she had a boat, she could sail across the Atlantic Ocean. Right over on the other side was Casablanca. One day, she’d go there. See through the eyes of her father. She turned back towards shore. Kate had got out of the water already and was beachcombing. It was one of her sister’s compulsions. Collecting shells and small pebbles off the beach, leaves, tree bark, berries and stones from the woods. Their bedroom was filled with all Kate’s treasures from nature in baskets and bowls, even in some of the clothes drawers.

‘Oh, looky at my ring!’ Kate declared, holding up a stone with a hole all the way through it, as Susannah waded out of the sea. Kate slipped the stone on her finger. ‘I do, I do!’ She twirled on the sand. ‘I’m going to marry Johnny Carver! He said so to me.’

Shivering from the cold, Susannah looked at her sister in disbelief. ‘Oh no, Katie, his nose is always dirty. You don’t want to marry a boy with a runny nose!’

‘But his daddy has the biggest boat, and he’s going to be the best fisherman on the whole island. Just like Daddy was.’

Kate was always saying what a great fisherman their father was, like their mother did too. That he had been an island man through and through, and his family belonged here and nowhere else. That this was where they had to stay forever. Ever and ever.

But Susannah knew it wasn’t true. Their daddy had been an adventurer. He had gone right the other side of the huge Atlantic Ocean to a whole new continent to do his duty for his country. To be part of history. Her daddy was a man of significance, not only a fisherman. She wanted to tell Kate this, but there was no point. Kate didn’t understand.

As the sun set, the two sisters walked back to the house. Susannah was still damp from the sea, the scent of the ocean on her skin, and her eyes red from being in the water so long, but she felt better now she’d been in it. Kate was still chattering away about her future wedding to the runny-nosed Johnny Carver. Susannah didn’t hear the woods rustling until two boys jumped out on to the road in front of them. Kate gave out a scream in fright, but Susannah scowled. She wasn’t afraid. It was only Silas Young and his younger brother, Matthew. The boys came from one of the oldest fishing families on the island. Youngs and Olsens went way back. Their fathers had both fought in the war, but the boys’ father had come back. Most of the girls at school were as afraid as Kate of Silas. He would chase them around the yard, trying to get kisses from them.

‘Where you two girls been?’ Silas asked. He was only one year old than Susannah, but because he was so tall and lanky he looked almost like a grown man.

‘None of your business,’ Susannah said, as Kate put her hand in hers.

‘Bet they been skinny dipping in the sea,’ Matthew teased them. ‘Wait until I tell my mom and she’ll go and tell yours. Boy will you be in trouble for going naked in the ocean.’

‘We weren’t skinny dipping,’ Kate blurted. ‘We had our bathers on, see!’ She pulled up her top to show Matthew her wet swimsuit, falling right into his trap.

‘Nice boobies!’ Silas howled as Kate went red with mortification.

‘Leave us alone,’ Susannah said, furious, as the boys walked in step with them.

‘Or what?’ Silas said, as Matthew pulled on Kate’s damp ponytail.

‘Ow!’ she protested.

‘I sure do like your hair, Katie Olsen; it’s the colour of butter,’ Matthew said, giving it a tug again.

‘Hey, leave her alone,’ Susannah said, giving him a kick on the shin.

The boy hopped back in surprise.

‘Well, ain’t she the wild one,’ Silas said, all sly-like.

‘Leave us be, alrighty?’ Susannah said, grabbing her sister’s hand and tugging her on. They broke out into a run towards home.

‘Run on home, girly girls!’ Silas called after them.

By the time they got home, Kate was in tears. Susannah wiped her face with her sleeve outside the door. ‘Don’t mind those stupid boys, Katie,’ Susannah said. She was anxious their mother would notice Kate’s distress and ban them from going out so late again. If she couldn’t get into the ocean on a summer’s evening, she’d just die with boredom.

‘But why don’t they like us?’ Kate asked. ‘Why are they so mean to us?’

‘I don’t know! Why do you care? They’re idiots!’ Susannah said, exasperated. Sometimes Kate was so wet.

Susannah needn’t have worried. Their mother was hard at work at the lacing stand, and barely looked up when they came in. Susannah shooed Kate up to bed.

Her sister, as always, fell asleep as soon as Susannah turned off their lamp. But despite having been up so early, and having to get up so early tomorrow, Susannah couldn’t sleep. She could hear Mother down below, working the shuttle. All summer long, ever since the day in the library when Mrs Matlock had shown her the map, Susannah had been dying to ask her mother the details of what had happened to her father. But instinct warned her not to. A part of her understood. Her mother kept them so busy because she couldn’t let herself sink into the grief. The shuttle going back and forth, lacing yarn, twine, threads, whatever she could, to mesh nets and more nets. Susannah hated those nets. Because they trapped her mother, and they trapped her and Kate on Vinalhaven, in a house which always felt empty because of their father’s absence.

The Gravity of Love

The Gravity of Love The Island Girls: A heartbreaking historical novel

The Island Girls: A heartbreaking historical novel The Adulteress

The Adulteress A Small Part of Me

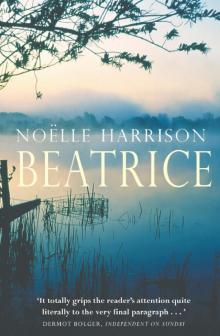

A Small Part of Me Beatrice

Beatrice