- Home

- Noelle Harrison

The Adulteress

The Adulteress Read online

For the apple gatherers

CONTENTS

The Adulteress I

The Adulteress II

The Adulteress III

The Adulteress IV

The Adulteress V

The Adulteress VI

The Adulteress VII

The Adulteress VIII

They bite from the same apple. It drops from her hand and rolls across the uneven floorboards. The crumpled bed sheets smell like a summer orchard. He kneels before her and presses his face in her soft belly, inhales her scent. He wraps his arms about her waist, his fingers making temporary indentations in her skin. She takes his hands in hers, and pulls him up so that he stands above her. She goes up on her tiptoes and kisses his lips lightly. She tastes of apple still – bitter, sweet, tart, true. He holds her in his arms, and they rock gently backwards and forwards. One pure moment passes and then he lifts her up. They tumble back onto the sheets, fragrant with their lingering desire. They are laughing, joy burning through their sweat. Together they are their whole sensual world. Perfectly complete, utterly fragile.

JUNE

We walk the land, Robert and I, his hand in mine, and I try to say something to comfort him in his loss. We have been married for five years and yet he has never spoken about his father to me, and since I have never met the old man, it is hard to know what to say. I cannot help wondering why it is we never visited him.

I catch sight of the house. It is a balmy day in September. There is warmth in the sun, a rare occurrence in Cavan. The thatch gleams in the sunlight, dazzling me as if it is real gold. I have never seen such a friendly-looking abode, so different from the house I was raised in.

My husband’s family home sits before me, with whitewashed walls, a bright-blue door and window ledges like two little eyes and an open mouth welcoming us in. It looks like a quaint cottage from a time long past. There are hens running across the yard, a mayhem of squawks, and even though we are here because Robert’s father has just died, there is such a celebration of life all around us. Hedgerows full of a variety of little birds, and red berries and blackberries peeking out of the greenery, brown cows and one dapple-grey horse grazing in the fields, a profusion of bright-pink fuchsia bells bushed around the side of the house. Something about the place is familiar, as if I have seen a picture of it in one of my childhood storybooks. The woods are Little Red Riding Hood’s, and the cottage Hansel and Gretel’s, and there is even a round tower on a distant hill, which looks like Rapunzel’s home.

Robert and I have always loved the city, vowed we would never leave it, but as we walk through his father’s fields and into the wood, something happens to us. I do believe we are bewitched by the landscape. Sunlight diffuses through the canopy of trees, still rich with leaves, showering us with amber warmth. I remember the sun of my childhood, how I loved its rays on my bare skin, how I felt the sun kissed me when my mother did not. We can smell the crisp whisper of autumn beginning as Robert and I pick sweet blackberries, feeding them to each other until our lips and chins are stained with juice. My husband appears more sensual to me than ever before. He softens, looking younger somehow, and less weighed down with all the worries he carries home from work every day. And the war . . . he is always talking about the wretched war. Is it being here, in Cavan, his real home, that makes him seem instantly happier, lighter, somehow more mine? Am I hoping he might forget about armies battling, bombs dropping, the possibility that Ireland might join in the war?

The air around us is humming with life, late lazy bees droning, dragonflies hastily mating, perhaps for the last time, and tiny tabby butterflies, dozens of them, fluttering around us. Everything surrounding us is light, and fast, thrumming in our ears, and yet we slow right down, each footstep measured in the dewy folds of grass. We walk beneath the trees, breaking through cobwebs, leaves spinning from their tendrils so that we know we are the only two who have passed this way in a long time.

I am not surprised when Robert suggests the move. On this glorious autumn afternoon, as we lie in a meadow overlooked by his newly inherited cattle, it seems the most natural thing to do to agree. More than anything I want to live somewhere that reminds me of nothing apart from fairy tales, and the sweet sugary side of childhood. Here, I say to myself, we can live in a dream world.

As we walk back up to the cottage we come across a rose bush bursting with velvet blooms, their sultry perfume arresting us. Ignoring my protests that he will prick himself with the thorns, Robert gathers a bunch of crimson roses, every now and then pausing to suck the tiny beads of blood off his fingertips. He presents them to me with a kiss, his lips blessing my forehead. I cradle a single scarlet rose in my palm, wishing to protect this symbol of our love. I look down at it. On one red petal is one red drop of blood.

NICHOLAS

The old house in Cavan is in pieces. Nicholas can see that once it was a pretty little cottage; however, years of neglect have turned it into little more than a derelict barn. And yet when he first saw the house he knew he had to buy it, even though it was practically uninhabitable and he was certainly no builder. But the cottage was familiar to him, as if he knew all the rooms by heart before he walked into them. He felt at home here, more than he had ever felt in the nine years they spent in Dublin. He tries to banish the memory of all the hard work he put into their home in Sandycove. The hours spent sanding the floors, choking in the dust, his eyes red-raw. There was the tiling that he had to redo because Charlie said he got the pattern wrong. The bloody bathroom. He never even liked it when it was done. Now here he is, starting all over again. Charlie said it was his choice to leave, but she gave him no choice. Nicholas has his pride.

He guts the house. The roof is good and the old stone walls are beautiful, but inside is a mess. The staircase up to the attic has woodworm and is completely rotten in places. The walls are wet with damp and mould. He tells himself he can do this. It is spring. He has the whole summer stretching ahead. Somehow it is his duty to bring this cottage back to life. Can a house have a heart and soul? he wonders. His piano stands lonely in the back room. Untouched. He cannot bear to play, although soon he will have to teach to make some money.

He looks out of the window at the green fields rolling away to infinity. He is in a landlocked county now and Nicholas misses the Irish Sea, those days when he and Charlie would walk all the way from Sandycove into Dun Laoghaire, and then down the pier to watch the ferry leave, discuss should they go too. He remembers looking across at the marina, and the bobbing yachts, and wondering what it would be like to spend your life sailing the sea, being as free as the seagulls wheeling above them.

‘The light is amazing here,’ Charlie would say and force Nicholas to quickstep so that she could get back home and paint, immediately translating the wide sea sky, grey, aqua and white, onto canvas. He preferred those early paintings, although he never dared tell her that. She thought she was getting better, but her pictures became more self-conscious, technically good, but they lost something.

Nicholas thinks of the Pacific Ocean crashing onto the beach at Turtle Bay and their honeymoon in Hawaii. They are lying in bed, entwined around each other like the limbs of a fantastical plant, and gazing at the huge waxen head of a flower outside the window. Its outrageous lushness, its dazzling pink brilliance seduces them. He rolls Charlie over, and her blue eyes sparkle the same colour as the ocean.

‘I love you,’ he says.

‘I love you too,’ she gazes at him with her true blue eyes, wrapping her legs around his waist and guiding him into her.

He was so young he thought this love was enough to keep them together forever. Yet it was only nine years ago. Not such a long time.

Nicholas sits back on his heels and closes his eyes, still holding the

spirit level in one hand, a pencil in the other. Pieces of wood lie about his feet, and he wonders what the fuck he is trying to do, buying a wreck in the middle of nowhere. Beads of sweat break out on his forehead, although it is damp in the attic. He can feel his heart beating fast, and the pain everywhere: behind his eyes, in his throat and chest, his legs, his groin and his back. His whole body pulses with need and he cries out like a wild animal. No one can hear him, in this crumbling old house in Cavan. Nicholas has chosen it as his place of refuge, his exile away from his old life, away from Charlie. He opens his eyes. Dust motes spin in the air, and a spider scampers across the splintered and rotten floorboards. He breathes in deeply. He can smell the heady fragrance of flowers. Hawaii. They are snorkelling together, their eyes beneath the surface of the crystal-clear blue, holding hands, floating, watching a sea turtle as she swims by. Then their minds are as one, in awe of the creature’s preternatural wisdom, the way she glides slowly through the water, taking all the time in the world to live. She looks at them – eyes so gentle, knowing, forgiving.

Nicholas snaps the pencil in half. Charlie. He cannot believe he will never hold her again, never touch her breasts, or feel her legs around his waist, her hips on his. But he would have to see her, yes. With the new face she wears, the distant, patronizing look in her eyes, detached smile, friendly as if he is a stranger. She behaves as if it were his fault. Has she no shame? Sometimes he wishes she were dead. Would it be easier then? She said that once. ‘Nick, you’re killing me.’ He didn’t understand what she meant, but he never asked.

Nicholas stands up, kicks the pile of wood across the attic. Suddenly he is filled with such a fierce rage he wants to destroy this house, pull it apart bit by bit, smash it up. He picks up the hammer and throws it through the window. The glass shatters, spraying him with tiny shards of glass. He is suddenly cold, shocked by his anger. He looks at his arms, speckled by little drops of blood. He is shaking, colder now than he has ever been in his life, his teeth are chattering. There is a huge hole in the window, and he will have to push all the glass out, get a new pane. More money. He stands by the broken window and again the aroma of flowers surrounds him. He recognizes the scent – roses. It is too early in spring for summer roses, red roses like his mother used to grow in her English country garden. Yet the smell is most definitely roses, overpowering, but not unpleasant. It calms him down. And then, as he is looking at the window, the rest of the glass falls in suddenly, as if someone has pushed it from the other side. He takes a step back, looks around the attic. Something doesn’t feel right.

He goes downstairs and takes a beer out of the fridge. He downs it in three gulps, each one gradually making him feel less spooked. He sits on the step of the back door, holding the empty bottle in his hand, and looking at his solitude, green fields, woods, an orchard. And yet he doesn’t feel alone. He is shivering again although it is warm in the sun. He twists around to look back into the shadows of the old house. The wind whispers through the hall, blowing some leaf skeletons, slowly dissolving residents since last autumn. His back is chilled and Nicholas places his hand on his heart, feels its faint beat through his shirt. He is surviving without Charlie – barely though, barely at all.

JUNE

I miss the sea. It is so very quiet here. Robert says I will soon get used to it and the place will grow on me. This is what he tells me, but I find it hard to imagine. There is a permanent chill in the air. I can feel it in my bones. And it is so damp my hair is in a constant frizz. The skies are filled with grey clouds, promising to rain, or having just rained, and a dark gloom enshrouds me all the hours of the day. I even miss London, but more so I miss the sea, the waves, its open lunacy, so different from the brooding corners of this country.

In Cavan the grey blanket of mist and rain has not lifted once since we moved in. Of course it rains in Dublin too, but the weather there can be brilliant sunshine one moment, strong sea breezes the next, and then a short, sharp burst of hard, drenching rain. There is nothing monotonous about it.

I was the wife of a city man, and now I am a farmer’s wife. We no longer live in a small rented flat, but in a thatched farmhouse on about fifty acres of land. We have ten bullocks, two cows, three little pigs, one horse and about thirty hens. I am a little daunted by this, for the farm is a kingdom all of its own and one I know nothing about. Robert rises early, returns for dinner and then goes back out again until dark. I am constantly busy learning all the duties a farmer’s wife has. If it were not for Oonagh Tobin, a neighbour’s daughter, I would be completely lost. She is a kind and patient teacher, but sometimes I feel so frustrated when I see her doing something easily and quickly, yet I cannot get the grasp of it. I am sure she believes I am a useless article. The first morning she had to show me how to bake a loaf of the brown soda bread they like to eat here. I will never forget her expression of surprise and then pity when she realized I had never done it before. I wanted to run away from her into my room and hide. I wanted to read a book.

She thinks I cannot cook. But I can. It is just that I make food with ingredients we cannot get here. I can bake so many different kinds of cakes – Madeira, rich fruitcake, chocolate gateau, Battenberg, Bakewell tart, Victoria sponge. I can even make a perfect lemon soufflé. Oh gosh, I can smell it now, taste it melting in my mouth, the light angelic spongy topping, followed by rich creamy-lemony filling. But what use have I of a lemon soufflé in Cavan? I have not seen a lemon since I came here. And when I think of the lemons in Italy – the size of grapefruit – and their scent in the air in Sorrento, the bittersweet taste of limoncello still lingering on my lips. It is almost a form of torture to remember such sensory delights.

Ireland is at economic war with England. Robert warns me there will be an awful lot more work once the spring comes. There is compulsory tillage because of the emergency, so he will have to plough most of the land. He has no help apart from the Tobins. They live further away from the village than us, towards the large lake, which I can see on a clear day if I climb a little rise of land at the back of our house. Of course the glimmer of water makes me think immediately of the sea.

Our closest neighbours are the Sheridens. They live on the outskirts of the village. At the edge of our land there is a small wood, and it is this that separates us from the Sheridens’ property. If we were to walk through the wood, we would end up in their back garden. Their house is quite different from ours: tall, and grey stone with a slate roof. I noted to Robert that it was large.

‘That may be so,’ he said, ‘but we are better off in our house. When it gets really cold, our thatch will keep us cosy and snug. The Sheridens will be freezing.’

He said this with such satisfaction that it made me think he is not too fond of these Sheridens.

Some days as I churn the butter, my hands sore, my shoulders and back stiff, I wonder what I am doing here and remember my old desires and dreams. How can I bear this? For a brief moment I feel like throwing the churn to the floor and watching its golden entrails spill across the flagstones, greasy, half-made, unfinished. Wasteful. I see myself running out into the yard, the hens flying about me in panic, the rain hammering down upon me.

‘Robert!’ I would cry out. ‘Robert!’

I would find him in a black boggy field, battling against the elements, wet and old-looking in a coat of his father’s. I would search for the dashing city man I married.

‘Take me home!’ I would command him, like my mother so often commanded my father.

I would see our old life in London, illuminating the donkey-grey sky like a celestial vision. Dinner parties, red buses, smoky tea rooms and train stations, the pictures, my sister Min laughing gaily and her husband Charles, smoking a pipe, stroking her hair affectionately, little Lionel the dog curled up asleep at her feet.

This second of regret is long. Its suppression is hard, for even if I did demand this of Robert, a return to our old life in London is impossible. Our London is gone forever. Our London has been destroyed by th

e war.

On these days I stop churning for a moment and look out at the lines of rain as they appear horizontal in the sky. I shiver in the damp kitchen. I scold myself. Remember, June, how lonely you were until you met Robert. Remember how you envied Min her married life. Remember how you longed for a husband too.

I repeat my farmer’s wife’s refrain like a prayer. ‘I will be a perfect wife. I will be the perfect wife. I will be Robert’s perfect wife.’

I have always put one hundred per cent into everything I do. Mummy, and maybe even Minerva, thought I would be a dusty spinster for the rest of my life. A classical scholar. A bluestocking. How surprised my mother was to learn that I had met the right match. My Irish English gentleman.

To be perfect is to be without fault or defect, to be perfect is to be complete. Let me tell you a story of imperfection, of a love’s incompletion and a wife’s undoing. Let me tell you about an adulteress.

It all began when my sister and I were children. How far from the tree does the apple fall? We grew up in Devon in a big white house, overlooking Torbay. What a fearless duo my sister and I were. We were like two little porpoises, splashing in the churning sea, rocked and cradled by the ocean. They were the summers when we were all together as a family. And Daddy would roll us along the beach, line us up saying, ‘You two look like peas in a pod.’

Yet it wasn’t true. We were the same height and proportion, but how different our colouring and our faces were. And our temperaments. One like Mother, and one like Father. When we were little, Father said we were the image of two angels by Raphael, with our curls – mine fair, Min’s dark, but both mops refusing to grow longer than our collars, instead getting thicker and thicker. It used to drive Mother insane, trying to get the brush through our hair every night.

Min and I took it in turns to sit on Father’s lap and he would play ‘This is the way the farmer rides’, and even though you knew what was going to happen, you didn’t know when until you were dropped through his legs, nearly on the ground, screaming with delight and fear. But Daddy would be holding you in his hands, one in each armpit, as you howled with laughter, helpless, all his.

The Gravity of Love

The Gravity of Love The Island Girls: A heartbreaking historical novel

The Island Girls: A heartbreaking historical novel The Adulteress

The Adulteress A Small Part of Me

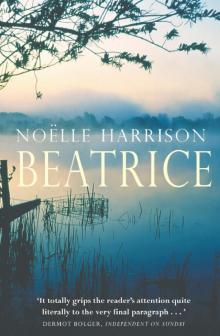

A Small Part of Me Beatrice

Beatrice